The 3-Year Practice Rule is no longer a legal debate. It is a nationwide directive that is now reshaping State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025.

In its landmark judgment dated May 20, 2025, the Supreme Court of India mandated that only those with a minimum of three years of court practice can appear for civil judge recruitment. This decision has not just redefined judicial eligibility, it has triggered ripple effects across State Judicial Exams, coaching institutions, and law universities.

For aspirants, this means recalibrating timelines and expectations. For State Public Service Commissions (PSCs), it demands urgent updates in eligibility notifications. For educators and coaching institutes, it is a curriculum shift that cannot wait.

In this blog, we break down how the 3-Year Practice Rule will:

- Change judicial exam eligibility in every Indian state

- Reshape how coaching institutes prepare candidates

- Affect final-year law students and recent graduates

- Impact notification cycles and PSC logistics

- Trigger broader reform demands in India’s legal education ecosystem

This is your guide to understanding and adapting to one of the most significant reforms in State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 and India’s judicial services landscape.

What the Supreme Court Actually Said About the 3-Year Practice Rule?

The Supreme Court of India delivered a defining verdict in the case of Renu v. District & Sessions Judge, Tis Hazari, cementing the 3-Year Practice Rule as a non-negotiable eligibility criterion for civil judge (junior division) appointments across India.

The Court interpreted Article 233(2) of the Constitution to mean that a person must have actual, in-court practice as an advocate for at least three years to be eligible. This invalidated state rules or recruitment policies that allowed fresh law graduates to appear directly for the judiciary.

Quoted from the Judgment:

“The expression ‘has been for not less than seven years an advocate’ under Article 233(2) must necessarily mean actual, substantive practice in a court of law… eligibility cannot be reduced to mere enrollment with no courtroom exposure.”

This directive applies uniformly, regardless of whether a State PSC had previously allowed freshers. The Court emphasized that judicial officers must have firsthand courtroom understanding, and that the law never intended to allow graduates with no litigation experience to decide civil or criminal matters.

Another Key Excerpt:

“Judicial service cannot be the first exposure to the functioning of a court. It must follow a foundational period of learning through practice.”

This is not simply a policy shift. It is a constitutional directive that mandates immediate reforms across all State PSCs — and has redefined State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 as a whole.

Read About the Constitutional Interpretation of Article 233

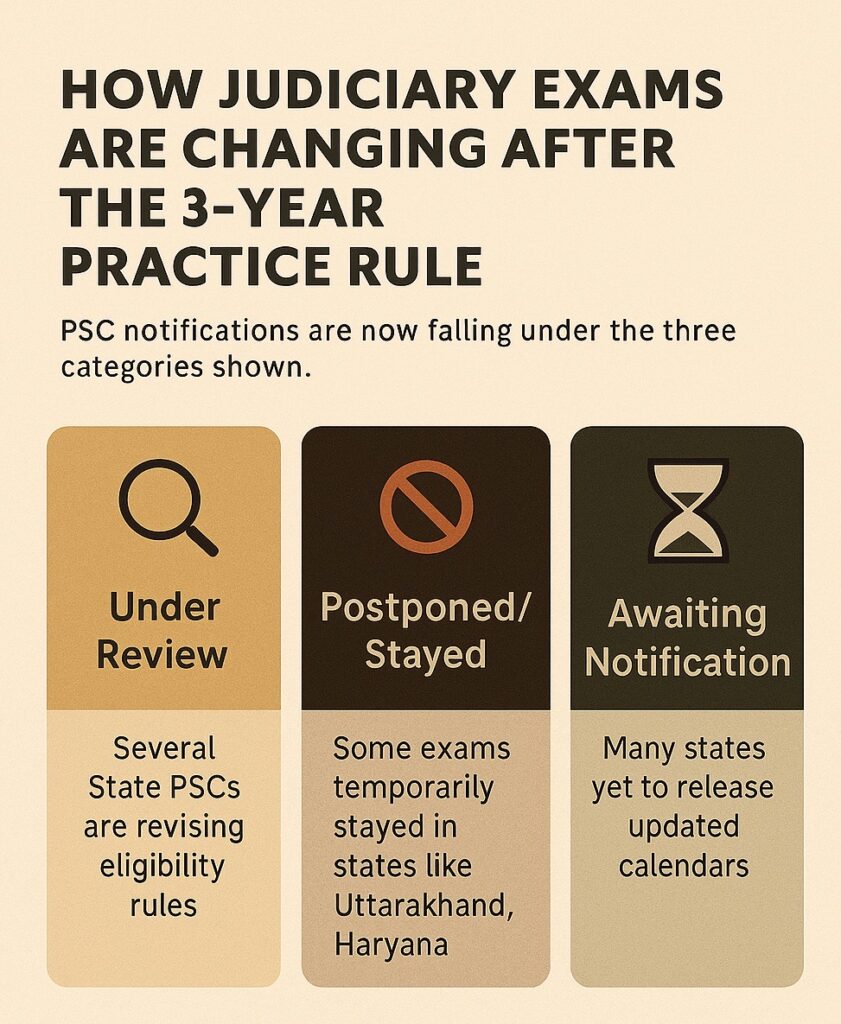

How Will State Judicial Exams Be Affected?

The Supreme Court’s ruling on the 3-Year Practice Rule has triggered a wave of changes across State Judicial Service Commissions. Though the mandate applies uniformly under Article 233(2) of the Constitution, the process of enforcement now falls to individual states — and that process is already underway.

State Notifications Being Withheld or Reviewed

Following the judgment, multiple State Public Service Commissions (PSCs) are reassessing their recruitment policies. For example:

- Uttarakhand Judicial Service Examination results have been put on hold.

- MPPSC (Madhya Pradesh) and Delhi Judicial Services have not issued new exam calendars post-verdict.

- In Haryana, the High Court has stayed selection processes pending eligibility reconsideration.

States that previously allowed fresh graduates are now expected to revise their frameworks entirely in line with the new State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 standard.

Final-Year Law Students Now Ineligible

One of the most immediate consequences is that final-year law students are no longer eligible to appear for judicial service exams. The Supreme Court clarified that eligibility requires both a completed law degree and a minimum of three years of courtroom practice.

This change directly affects current aspirants and upcoming law graduates. Law schools and coaching centres must now update career roadmaps, timelines, and preparation models.

Uniform Mandate, Uneven Implementation

While the directive is constitutionally binding across India, states will adopt it at their own administrative pace:

- Some PSCs are expected to notify amendments promptly.

- Others may delay implementation until the next exam cycle.

Candidates should anticipate delays and keep a close watch on their respective PSC websites and court circulars for real-time updates.

Anticipated Legal Challenges and Transitional Uncertainty

Coaching institutes and affected candidates have begun exploring legal remedies. Petitions may challenge:

- Whether the rule applies retrospectively or prospectively

- The status of candidates who already applied under earlier eligibility rules

- The timeline of implementation by each state

Even though the Supreme Court’s judgment is binding, new writ petitions and state-level litigations may temporarily cloud the landscape of State Judiciary Eligibility 2025.

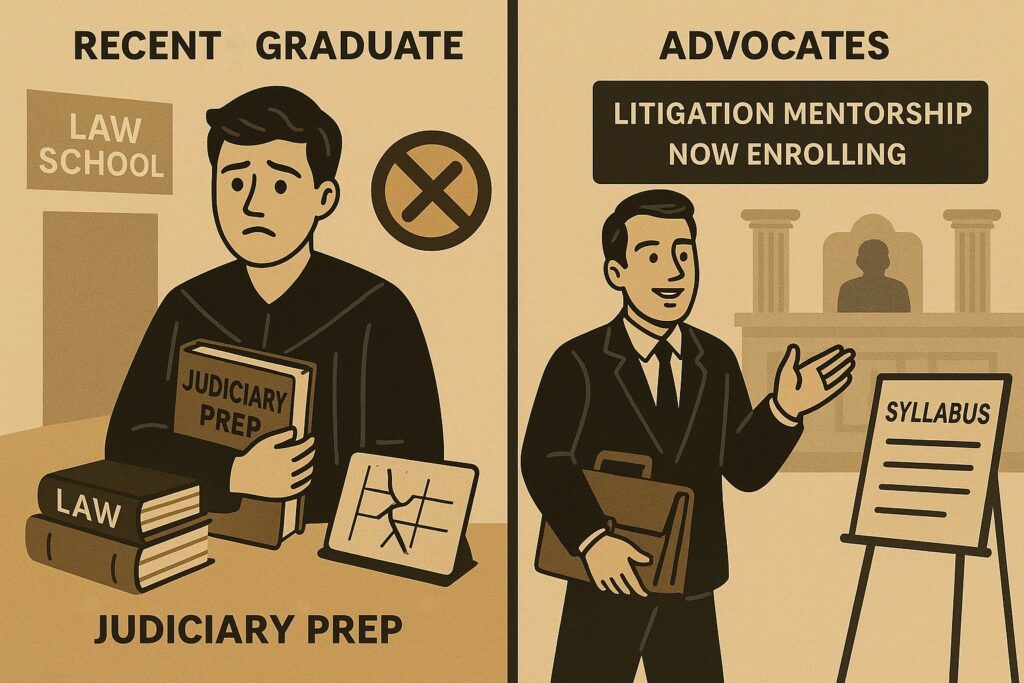

Impact on Aspirants and Coaching Institutes

The Supreme Court’s ruling has not only shifted legal policy but also shaken the ecosystem that supports judicial exam preparation. From students mapping out career timelines to institutions designing long-term study plans, the entire landscape surrounding State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 is being restructured.

Aspirants Must Now Strategically Plan Their Legal Practice

Until now, many law graduates treated judicial exams as the immediate next step after college. This judgment changes that narrative completely. Aspirants must now:

- Begin courtroom practice immediately after graduation

- Document their experience meticulously to meet eligibility proofs

- Focus on real-time litigation exposure, not just academic merit

This new State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 framework adds a layer of practical training to what was earlier just an academic goal. Many aspirants now face a dual challenge: surviving the early years of legal practice while continuing to nurture their judicial aspirations.

“For many fresh graduates, the judgment feels like a push to first engage with the system before aspiring to judge it.”

Coaching Institutes Must Rethink Their Business Models

Judiciary coaching centres, particularly those offering integrated LLB + judiciary tracks, now need to adapt quickly. Key changes include:

- Reworking their curriculum to focus on litigators, not final-year students

- Creating bridge modules to help practicing advocates stay connected to exam content

- Delaying enrollments or launching new verticals like litigation mentoring

“Judiciary coaching can no longer revolve around books alone, we now have to guide aspirants through the realities of the courtroom.”

Constitutional Interpretation of Article 233

The Supreme Court’s decision in Renu v. District & Sessions Judge, Tis Hazari (2023) hinges on a careful, purposive interpretation of Article 233(2) of the Indian Constitution. This provision now serves as the constitutional backbone of the eligibility framework for State Judiciary Eligibility 2025.

What Article 233(2) Actually Says

“A person not already in the service of the Union or of the State shall only be eligible to be appointed a district judge if he has been for not less than seven years an advocate or a pleader and is recommended by the High Court.”

The phrase “has been for not less than seven years an advocate” was previously interpreted loosely by several State PSCs. Law graduates were allowed to appear for judicial service exams, provided they fulfilled the 7-year condition by the time of appointment—not necessarily at the time of application.

This liberal reading has now been firmly rejected by the Supreme Court, solidifying State Judiciary Eligibility 2025 around the requirement of active courtroom practice at the time of application itself.

Supreme Court’s Interpretation in Renu v. District Judge

In its landmark ruling, the Supreme Court clarified the real meaning of Article 233(2) and reset how eligibility for judicial appointments must be assessed:

- The status of an advocate must exist at the time of application, not just at the time of appointment.

- Mere enrollment with a Bar Council does not amount to actual practice.

- Courtroom experience must be active, consistent, and substantial, not theoretical or symbolic.

“The phrase ‘has been an advocate’ denotes actual practice, not merely enrollment or passive registration,” the Court observed.

Purposive vs Literal Interpretation

“This judgment showcases a classic example of purposive interpretation, looking beyond the literal text to preserve the true constitutional intent.”

The message is clear:

Only those with real litigation experience are fit to serve as judges.

Textbook knowledge cannot substitute first-hand courtroom exposure, client engagement, or real legal strategy. These are now seen as essential prerequisites under State Judiciary Eligibility 2025.

“Those unfamiliar with courtroom realities may lack the sensitivity, maturity and balance expected of a judge,” the judgment warns.

Final Takeaway from the Judgment

This is more than a procedural amendment; it marks a jurisprudential realignment rooted in constitutional fidelity. The ruling restores the original spirit of Article 233(2) by firmly establishing that State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025 must be grounded in:

- Real-world legal experience

- Maturity gained through courtroom practice

- Empathy shaped by sustained advocacy

The Court made it unequivocal: passive knowledge of the law is insufficient. First-hand exposure to judicial functioning, client interaction, and courtroom dynamics is now a non-negotiable foundation for those aspiring to join the Bench.

As the judgment notes:

“Those unfamiliar with courtroom realities may lack the sensitivity, maturity and balance expected of a judge.”

By reinforcing the purposive interpretation of Article 233(2), the Supreme Court has shifted the focus of recruitment from mere academic eligibility to substantive legal engagement — setting new benchmarks for State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025 and beyond.

Implementation Challenges and Transitional Confusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling is constitutionally binding, but implementing it uniformly across all states is far from a simple task. As of now, the transition is already creating confusion among aspirants, State PSCs, and coaching institutions, all grappling with how to align with the updated framework of State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025.

Patchy and Uneven Enforcement

While some states like Delhi and Haryana promptly suspended upcoming judiciary exam notifications for updates, others have yet to respond formally. This has led to inconsistent eligibility announcements and revised timelines.

For instance, the Chhattisgarh Public Service Commission (CGPSC) issued clarifying notices after aspirants raised concerns over the eligibility conditions during an ongoing application cycle.

Such inconsistency not only undermines fairness, but also highlights the absence of a centralized strategy from either the judiciary or executive branch.

Uncertainty Among Aspirants

Thousands of law students and recent graduates now find themselves in limbo. Many who had prepared under the previous framework must now postpone their judicial aspirations by at least three years, with no concrete roadmap for how to navigate this detour.

“I just quit my law firm job to focus full-time on judiciary exams. What now?”

This is the question echoing through coaching centers, law classrooms, and Bar Council forums across the country.

Need for Clear Administrative Action

To stabilize the transition and uphold transparency in State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025, states must now:

- Update eligibility criteria in all recruitment notifications

- Establish clear implementation timelines aligned with the new mandate

- Coordinate with High Courts for uniform interpretation

- Launch awareness initiatives, including outreach programs and FAQs for aspirants and institutions

Until then, the legal community will continue to face anxieties, inconsistencies, and confusion over what should be a well-structured transition.

How Should Aspirants Adapt to the 3-Year Practice Rule?

While the ruling has disrupted long-standing exam strategies, it also introduces a more grounded and practice-oriented path to the judiciary. Aspirants must now reorient their timelines, expectations, and strategies with clarity instead of panic, especially in light of the changes affecting State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025.

Acknowledge the Shift

The judiciary exam is no longer a purely academic sprint. It’s now a long-distance professional race, where litigation experience is a prerequisite, not a bonus.

Aspirants must now factor in 3 years of courtroom exposure before they are even eligible to apply. This demands a shift in mindset from rote preparation to real-world engagement.

Enter the Courts, Strategically

Not all practice is equal. Candidates should:

- Work under senior advocates or at law chambers with strong drafting and arguing exposure

- Focus on civil and criminal procedure, interim applications, and trial court functioning

- Maintain daily appearance records and a practice journal, which may help in future scrutiny or self-assessment

Don’t Lose Touch With the Syllabus

3 years in litigation doesn’t mean the exam syllabus becomes irrelevant.

Judicial aspirants should:

- Allocate weekend time for law revision and mock tests

- Consider short online modules or evening classes to stay sharp

- Follow legal developments, SC rulings, and High Court case law to build judgment-writing and reasoning skills

Recommendations for Law Schools and Bar Councils

The Supreme Court’s 3-Year Practice Rule has created an immediate challenge for law schools and Bar Councils: how to bridge the academic world with courtroom realities.

India’s legal education system has long been criticized for being overly theoretical. With the judiciary now requiring practical litigation experience before eligibility, academic institutions must rethink how they prepare students for judicial careers.

Law Schools Must Pivot from Theory to Practice

Law schools can no longer function as passive degree-issuing bodies. They must actively build legal readiness for the courtroom.

“Law schools must become incubators of courtroom readiness, not merely institutions that produce LLB degree holders.”

To realign with the new eligibility standards, institutions should consider:

- Introducing mandatory courtroom internships with trial and appellate lawyers

- Embedding clinical legal education into the core curriculum

- Hosting moot courts that mirror real case scenarios, not just competitions

- Creating alumni mentorship programs to help fresh graduates transition into litigation

These steps will help ensure graduates don’t simply finish their LLB, but leave with a foundation to start legal practice and eventually qualify for judicial roles.

Bar Councils Must Provide Early-Career Support

The role of Bar Councils becomes crucial in this transition. Without adequate support, many young advocates may drop out during the initial 3-year period due to poor exposure or income.

Recommendations for Bar Councils include:

- Setting up practice incubation centers for first-generation lawyers

- Offering stipends or litigation scholarships to early-stage practitioners

- Creating CPD (Continuing Professional Development) programs focusing on trial advocacy, ethics, and legal research

- Monitoring compliance with the actual practice requirement, not just enrollment

Together, these reforms can smoothen the path from legal education to courtroom competence, aligning directly with State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025.

Coaching Institutes: Rethinking Curriculum and Strategy

The Supreme Court’s 3-year practice mandate has forced judiciary coaching institutes across India to reassess their role in shaping future judges. The days of fast-tracked preparation for final-year law students are over. Instead, coaching strategies must now evolve to meet the practical needs of a courtroom-first eligibility landscape.

Shift in Target Audience

With State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025 now contingent upon litigation experience, coaching centers can no longer cater primarily to fresh graduates. The new audience includes:

- Young advocates already enrolled in Bar Councils

- Litigators seeking structured judicial prep post-practice

- Law graduates navigating practice while preparing for the Bench

Curriculum Overhaul

Institutes must redesign their offerings with a hybrid model:

- Litigation Mentorship Tracks: Modules on real case analysis, client interaction, and court diary management

- Courtroom Exposure Workshops: Tie-ups with chambers for drafting assistance, filing training, and observing proceedings

- Eligibility Timeline Mapping: Helping students plan 3-year practice pathways that align with future exam calendars

Academic Heads Speak

“Judiciary coaching can no longer rely on books alone — we now guide aspirants through the realities of practice,” says the founder of a top coaching institute in Delhi.

Institutional Accountability

It’s time for coaching centers to move from “exam-cracking” to “judge-preparing.” This means teaching not just constitutional theory, but also professional responsibility, advocacy ethics, and procedural stamina.

In the evolving system, coaching institutes that don’t upgrade risk becoming irrelevant. Those that do, however, will play a pivotal role in building a more qualified and empathetic judiciary.

Final Takeaway for State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025

The 3-Year Practice Rule is more than just a policy shift; it marks a foundational reset in the way judicial merit is evaluated in India. By rooting State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025 in courtroom experience rather than classroom performance, the Supreme Court of India has realigned recruitment with the core demands of justice.

This move brings sharper clarity to what it takes to be a judge in today’s India: not just legal knowledge, but legal maturity. Not just credentials, but credibility earned through practice. The verdict places equal emphasis on integrity, experience, and empathy, qualities that can only be developed through years of genuine litigation work.

For aspirants, this is not the end of the road — it’s the beginning of a more meaningful journey. For law schools, PSCs, and the wider legal community, it’s a call to reimagine how we prepare future judges.

This ruling doesn’t just meet the moment. It sets a new constitutional benchmark & one that is long overdue.

FAQs on the 3-Year Practice Rule and State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025

Does the 3-Year Practice Rule apply to all states in India?

Yes. The Supreme Court’s judgment is constitutionally binding and applies uniformly across all states. However, the pace of implementation may vary, depending on how each State PSC revises its eligibility criteria.

Can final-year law students still appear for judicial service exams?

No. As per the ruling, only candidates who have completed their LLB and have practiced as advocates for at least 3 years are eligible to apply. This disqualifies final-year students from applying under the new State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025 framework.

What counts as valid courtroom practice?

Valid courtroom practice involves active participation in litigation — appearing before courts, drafting pleadings, filing cases, and engaging in substantial legal work. Mere enrollment with a Bar Council is not sufficient.

Will there be any relaxation or transitional provision for those already preparing under the old criteria?

Currently, the judgment does not provide for any transitional relief. However, writ petitions in some states may attempt to seek clarifications or limited exceptions. Aspirants should closely monitor PSC notifications and court developments.

How should law graduates plan their careers post-judgment?

Graduates should immediately begin court practice under experienced litigators. Maintaining appearance records, engaging in live casework, and keeping up with exam syllabi simultaneously will be essential. This dual track will prepare them for judicial services under the updated State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025.

References

- Renu & Ors vs District & Sessions Judge, Tis Hazari & Anr – Full Judgment

- Supreme Court Observer Analysis

- Economic Times Commentary

- LiveLaw Report

Still Have Questions About State Judiciary Eligibility in 2025?

Whether you’re a law graduate recalibrating your journey, a coaching institute reworking your curriculum, or a law school seeking clarity on the 3-Year Practice Rule, we’re here to help.

At LexNova Consulting, we offer tailored legal insights, compliance strategy, and academic guidance aligned with India’s evolving judicial frameworks.

Reach out to us. Let’s navigate this legal transformation together.

📞 Contact Our Legal Experts:

✉️ Email: contact@lexnovaconsulting.com

🌐 Website: www.lexnovaconsulting.com

Serving clients globally

📩 Or use the form below and we’ll get back within 24 hours: 👉Let’s Talk Law.

🛡️ All communications are confidential. We do not share personal information with third parties.

Disclaimer

This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. While LexNova Consulting strives to ensure the accuracy and relevance of all content, readers are advised to consult a qualified legal professional for advice tailored to their specific circumstances. References to laws, judgments, and official sources are current as of the date of publication. LexNova Consulting is not responsible for any decisions made based on this content.