Introduction

In July 2025, scientists in the UK and Israel made headlines by creating synthetic human embryos without using sperm or egg. These lab-grown embryos, formed from stem cells, mimic the earliest stages of human development. The implications were immediate, controversial, and legally perplexing. For the first time, life could begin without fertilization.

Yet no jurisdiction, not India, the UK, the US, or the UAE, has comprehensive legal frameworks for such developments. Are synthetic embryos property, patentable innovations, or do they possess some form of legal personhood? As bioengineering accelerates beyond law’s current boundaries, it’s time for global legal systems to confront the ethical, regulatory, and constitutional questions surrounding synthetic embryos.

Welcome to a legal frontier: Synthetic Embryos and the Law.

What Are Synthetic Embryos?

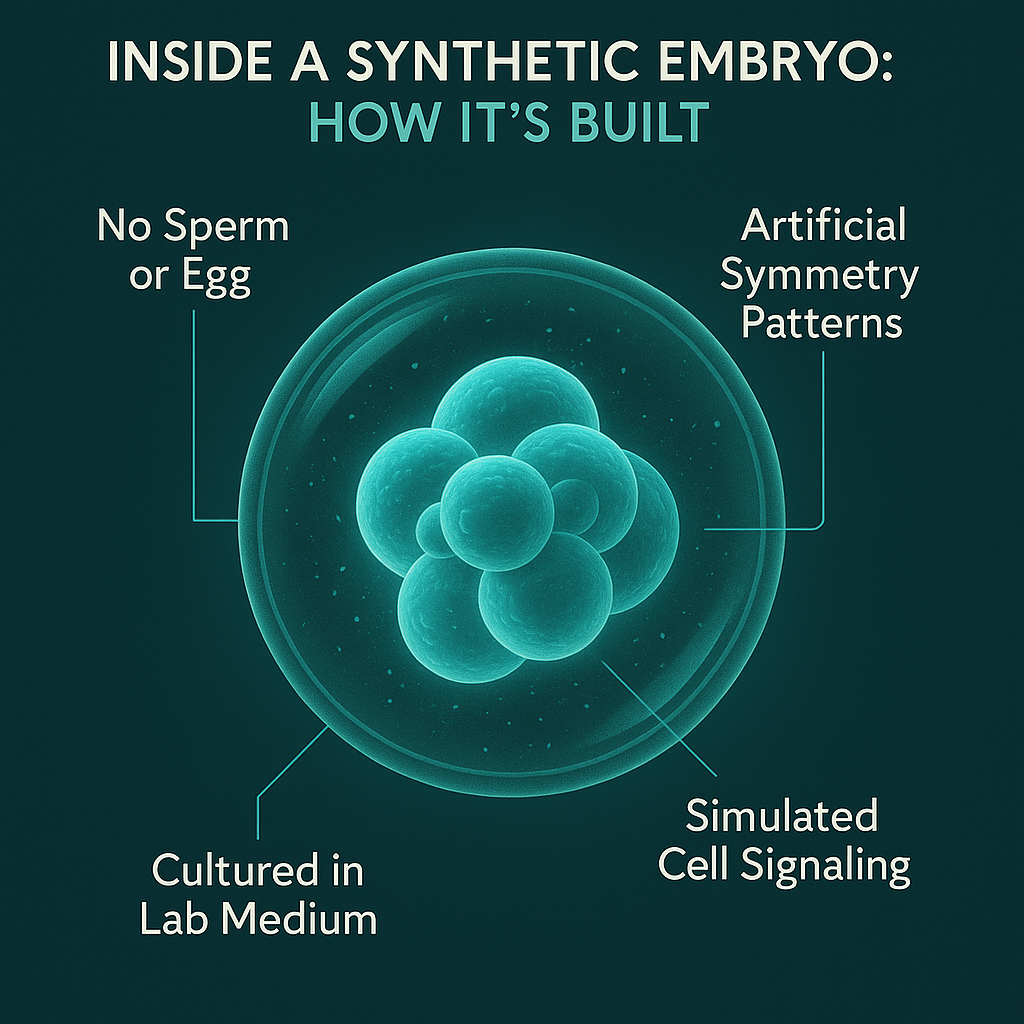

Synthetic embryos (also called embryo models or embryoids) are lab-grown structures made from pluripotent stem cells. Unlike embryos created via in vitro fertilization (IVF), they do not originate from fertilized eggs or sperm. Instead, scientists coax stem cells to self-organize into structures that resemble early human embryos.

These models include primitive brain-like tissues, early organ precursors, and even early developmental membranes. Importantly, they can mimic the development up to the 14-day mark, the ethical limit followed in most embryonic research.

Comparison: Natural vs Synthetic Embryos

| Feature | Natural Embryo (IVF) | Synthetic Embryo |

| Origin | Sperm + Egg | Stem Cells Only |

| Genetic Identity | Inherited from parents | Engineered or random stem cells |

| Implantation Potential | Yes (in womb or surrogate) | Not yet proven viable |

| Legal Framework | IVF laws apply | No current regulation |

Synthetic embryos currently serve research purposes: understanding miscarriages, birth defects, and organ development. But as technology evolves, their potential reproductive or therapeutic applications demand urgent legal scrutiny.

The Legal Vacuum

Despite their scientific significance, synthetic embryos exist in a legal limbo. No statute worldwide defines their status. This gap creates dilemmas:

- Bioethical uncertainty: Are they alive? Do they have rights?

- Intellectual property: Can labs own them?

- Criminal law: Is destroying a synthetic embryo a crime?

- Fertility law: Can they be used in surrogacy or ART?

In India, the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021 and the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 do not mention synthetic embryos. Similarly, UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, 1990 predates this innovation.

The result? Courts and regulators are left to interpret principles without statutory guidance. Constitutional protections (like right to life or privacy) may extend to certain biological forms, but synthetic embryos fall in a grey area.

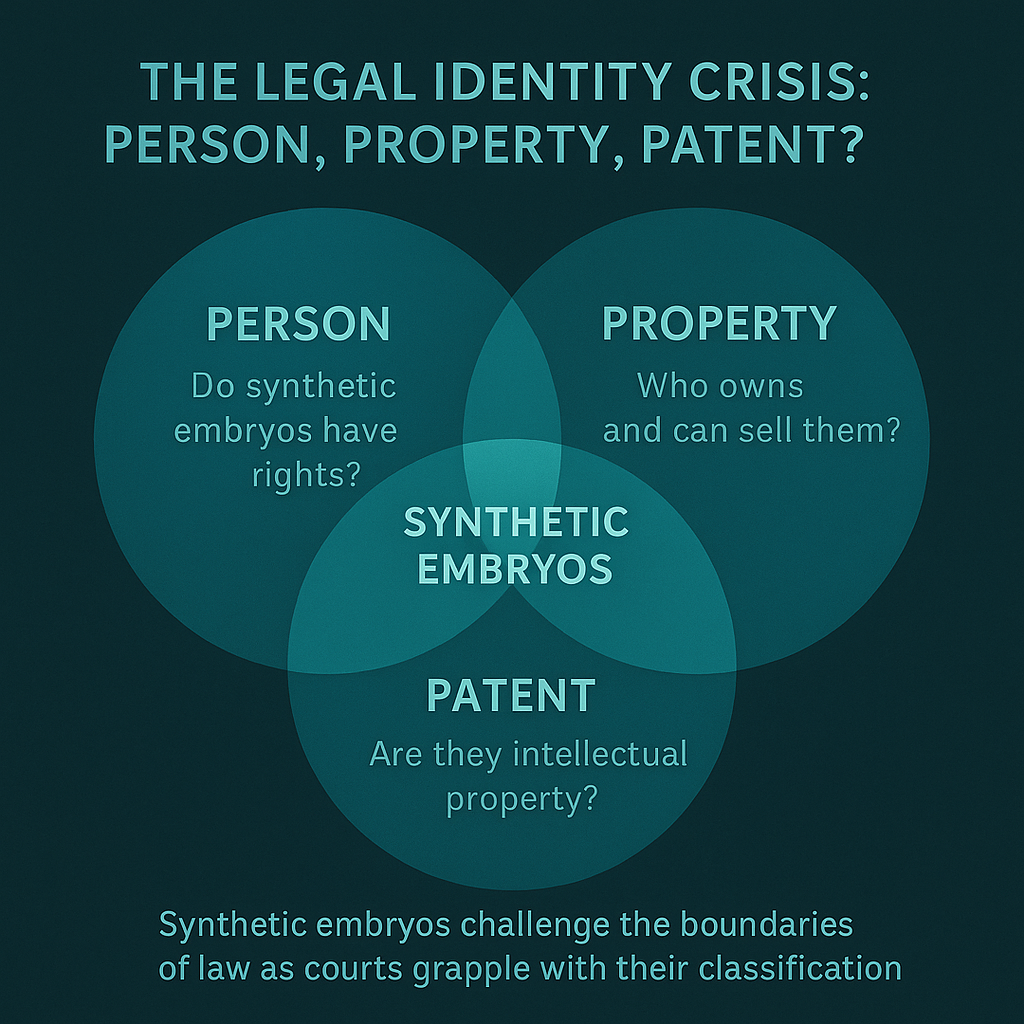

Person, Property, or Patent?

The central legal question is classification: what are synthetic embryos in the eyes of the law?

| 1. Personhood Argument Some bioethicists argue that once an entity mimics human development, it may deserve certain protections. This echoes earlier debates in Roe v. Wade (now overturned), and in India’s abortion jurisprudence balancing fetal rights and women’s autonomy. |

| 2. Property and Ownership Others propose they are mere tissue constructs, akin to organoids. But can something mimicking life be owned? In Moore v. Regents of University of California (1990), a patient’s cells were patented without his consent. The court denied ownership but flagged ethical gaps in biotechnology commercialization. |

| 3. Patentability of Life Forms In the US, Diamond v. Chakrabarty (1980) held that genetically engineered bacteria were patentable. Would that extend to embryo models? The USPTO and WIPO remain cautious, though patent applications on embryoid structures are rising. |

Comparative Legal Review

United Kingdom

The UK’s HFEA prohibits embryo research beyond 14 days and requires licensing for human embryo creation. But synthetic embryos, not derived from gametes, sit outside this framework. In June 2025, the HFEA launched a public consultation on whether synthetic models should be regulated similarly.

United States

Federal funding bans on embryonic research exist, but private labs like those in California continue embryoid studies. NIH guidelines require ethics board approvals. No federal law regulates synthetic embryos per se, but state-level restrictions on embryo research may apply.

India

No regulation addresses synthetic biology or embryo models. The ART Act focuses on gamete-based reproduction. India’s ICMR has yet to issue any binding guidance, though its 2024 draft bioethics guidelines mention synthetic biology as a future area of concern.

European Union

Under Horizon Europe, synthetic biology is a funded priority, but embryo models fall into ethical scrutiny zones. The European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE) has warned that synthetic embryo research may require a pan-European legal definition.

UAE

The UAE allows IVF and stem cell research under Sharia-compliant guidelines. Synthetic embryos raise novel religious questions. The UAE’s Fatwa Council and Ministry of Health have not yet published positions, but increasing biotech investment signals future regulatory movement.

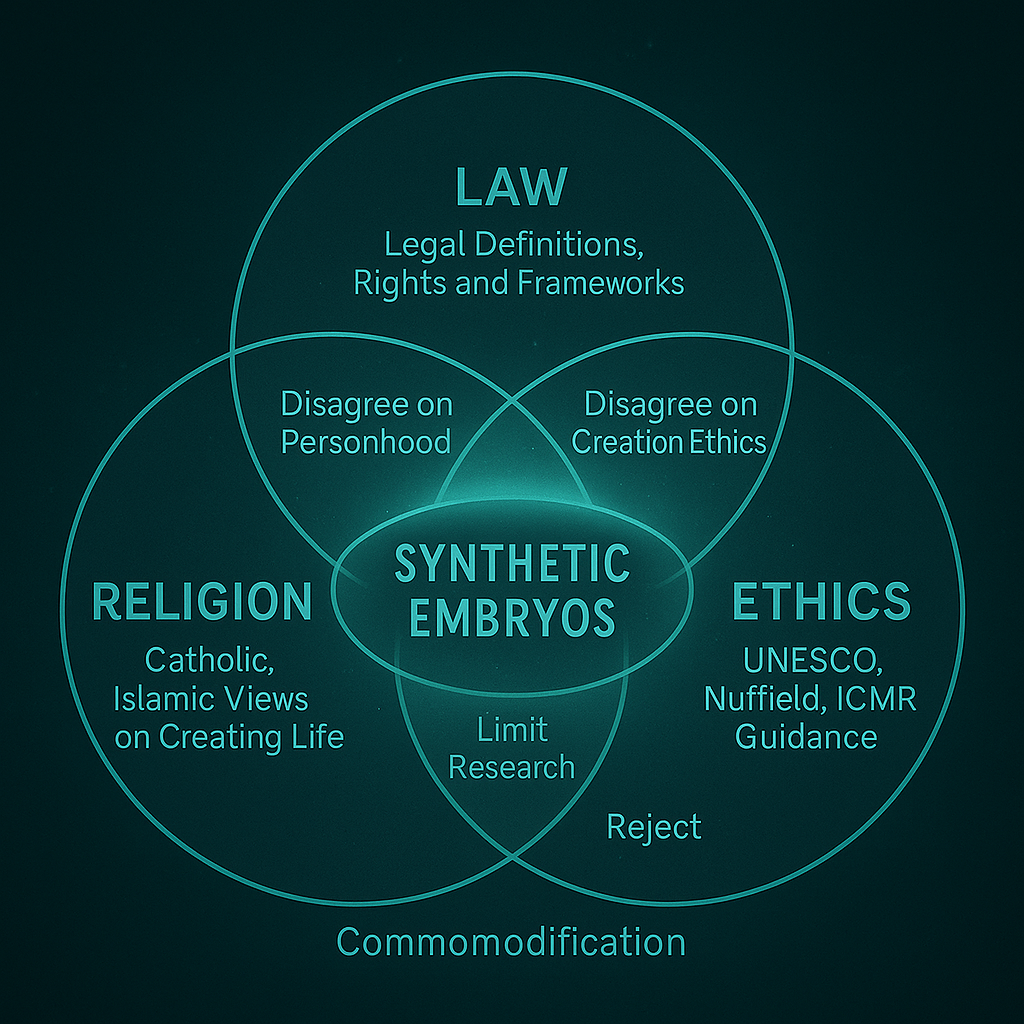

Religious and Ethical Crossroads

Religions differ on when life begins. Do synthetic embryos qualify?

- Catholicism: Rejects artificial embryo creation as a violation of natural law.

- Islamic Ethics: Emphasizes ensoulment at 120 days; synthetic life unclear.

- Hinduism: Views on embryonic life vary, but karma and non-violence principles apply.

UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee and the UK’s Nuffield Council both recommend precautionary approaches. Ethics boards urge “dignity-based” frameworks: regulating not just use, but the intent behind creating synthetic forms of life.

Policy Recommendations

To address this legal vacuum, global regulators should:

- Define Legal Status: Establish whether synthetic embryos are tissue, pre-life entities, or something novel.

- Guardianship Provisions: Like minors, synthetic embryos (if used in trials) may require legal guardians or custodians.

- Regulate Destruction: Prohibit unethical disposal or limit it to licensed labs.

- Patent Criteria: Disallow ownership of entire human-like forms; allow partial biotech innovations under ethical licensing.

- International Treaties: Like the Oviedo Convention or UNESCO Bioethics Declaration, a new instrument may be needed to harmonize global norms.

Final Takeaway

Synthetic embryos sit at the intersection of law, life, and science. As humanity redefines reproduction, personhood, and innovation, the law cannot remain silent. Without urgent regulatory clarity, courts may be forced to decide matters they are ill-prepared for.

LexNova Consulting urges policymakers, researchers, and biotech companies to approach this frontier with both caution and courage. We offer legal clarity in the fog of emerging bioethics.

References

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics — Stem Cell‑Based Embryo Models (SCBEMs)

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) – UK Regulatory Context

- ISSCR & Scientific Review – Synthetic Embryo Ethics Updates (2025)

Read Also:

- Adriana Smith: A Medical Ethics Crisis and Legal Wake-Up Call

- The Marital Rape Exception: Is India Ready to Repeal It in 2025?

Glossary

Embryoid: A structure resembling a human embryo, formed without sperm or egg.

Pluripotent Stem Cells: Cells that can become any type of body cell.

IVF: In Vitro Fertilization, a method of conception using egg and sperm in a lab.

Bioethics: Ethical principles governing biological and medical research.

Patent Law: Legal rights granted to inventors over their creations.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Laws and regulations vary by jurisdiction and are subject to change. For personalized legal counsel on health, bioethics, or intellectual property law, please contact LexNova Consulting.